Sunday, 30 September 2018

Vegan Plantain Curry

[[ This is a content summary only. Visit my website for full links, other content, and more! ]]

from Running on Real Food https://runningonrealfood.com/vegan-plantain-curry/

via Enlightened Marketing

40 Minute Full-Body EMOM Workout

[[ This is a content summary only. Visit my website for full links, other content, and more! ]]

from Running on Real Food https://runningonrealfood.com/40-minute-full-body-emom-workout/

via Enlightened Marketing

Paleo Pumpkin Pancakes

Start your day off right with these grain-free, pumpkin-packed, and oh so scrumptious Paleo Pumpkin Pancakes. These festive pancakes will spruce up your Fall breakfasts all season long. Whip up a batch today! Fall is finally here in Minneapolis! And I must say, it’s may absolute favorite time of year for ...

Start your day off right with these grain-free, pumpkin-packed, and oh so scrumptious Paleo Pumpkin Pancakes. These festive pancakes will spruce up your Fall breakfasts all season long. Whip up a batch today! Fall is finally here in Minneapolis! And I must say, it’s may absolute favorite time of year for ...

The post Paleo Pumpkin Pancakes appeared first on Fit Foodie Finds.

from Fit Foodie Finds https://fitfoodiefinds.com/paleo-pumpkin-pancakes/

via Holistic Clients

Saturday, 29 September 2018

How I Reduced My Cortisol Levels Naturally With Food & Light

Oh, relaxation, that elusive activity that is often talked about and rarely achieved in today’s world. We all know we have too much stress and need to reduce it, but the execution is so elusive! Most of us probably know that our cortisol levels may be off, but fixing this takes more that just a...

Continue reading How I Reduced My Cortisol Levels Naturally With Food & Light...

from Wellness Mama® https://wellnessmama.com/1570/reduce-cortisol/

via SEO Derby

Friday, 28 September 2018

Bronwyn King leads global pledge for tobacco-free finance, and more TED news

The TED community has been making headlines — here are a few highlights.

Tobacco-free finance initiative launched at the UN. Oncologist and Tobacco Free Portfolios CEO Bronwyn King has made it her mission to detangle the worlds of finance and tobacco — and ensure that no one will ever accidentally invest in a tobacco company again. Together with the French and Australian governments, and a number of finance firms, King introduced The Tobacco-Free Finance Pledge at the United Nations during General Assembly week. The aim of the measure is to decrease the toll of tobacco-related deaths, which now stands at 7 million annually. More than 120 banks, companies, organizations and groups representing US$6.82 trillion have joined the launch as founding signatories and supporters. (Watch King’s TED Talk.)

The Museum of Broken Windows. Artists Dread Scott and Hank Willis Thomas are featured in a new pop-up show grappling with the dangerous impact of “broken windows” policing strategies, which target and criminalize low-income communities of color. The exhibition, which is hosted by the New York Civil Liberties Union, explores the disproportionate and inequitable system of policing in the United States with work by 30 artists from across the country. Scott’s piece for the showcase is a flag that reads, “A man was lynched by police yesterday.” Compelled by the police killing of Walter Scott, Scott revamped a NAACP flag from the 1920s and ‘30s for the piece. Thomas’ contribution to the exhibition are poems, letters and notes from incarcerated people titled “Writings on the Wall.” The exhibition is open through September 30 in Manhattan. (Watch Scott’s TED Talk and Thomas’ TED Talk.)

The future of at-home health care. Technologist Dina Katabi spoke at MIT Technology Review’s EmTech conference about Emerald, the healthcare technology she’s working on to revolutionize the way we gather data on patients at home. Using a low-power wireless connection, Katabi’s device, which she developed with a team at MIT, can monitor patient vital signs without any wearables — and even through walls — by tracking the electromagnetic field surrounding the human body, which shifts every time we move. “The future should be that the healthcare comes to the patient in their homes,” Katabi said, “as opposed to the patient going to the doctor or the clinic.” Some 200 people have already installed the system, and several leading biotech companies are studying the technology for future applications. (Watch Katabi’s TED Talk.)

Does New York City have a gut biome? In collaboration with Elizabeth Hénaff, The Living Collective and the Evan Eisman Company, algoworld expert and technologist Kevin Slavin has debuted an art installation featuring samples of New York City microorganisms titled “Subculture: Microbial Metrics and the Multi-Species City.” Weaving together biology, data analytics and design, the exhibit urges us to reconsider our relationship with bacteria and redefine how we interact with the diversity of life in urban spaces. Hosted at Storefront for Art and Architecture, the project uses genetic sequencing devices installed in the front of the gallery space to collect, extract and analyze microbial life. The gallery will be divided into three spaces: an introduction area, an in-house laboratory and a mapping area that will visualize the data gathered in real time. The exhibit is open through January 2019. (Watch Slavin’s TED Talk.)

from TED Blog https://blog.ted.com/bronwyn-king-leads-global-pledge-for-tobacco-free-finance-and-more-ted-news/

via Sol Danmeri

Best Appetizers for a Healthy Game Day

Spice up the game with these delicious game day appetizers! All of your favorite game day flavors now with a better-for-you twist. Bring on the healthy appetizers! TOUCHDOWN! Searching for the perfect delicious AND healthy appetizer to bring to the next game day get-together? WE GOT YOU. Choose from the ...

Spice up the game with these delicious game day appetizers! All of your favorite game day flavors now with a better-for-you twist. Bring on the healthy appetizers! TOUCHDOWN! Searching for the perfect delicious AND healthy appetizer to bring to the next game day get-together? WE GOT YOU. Choose from the ...

The post Best Appetizers for a Healthy Game Day appeared first on Fit Foodie Finds.

from Fit Foodie Finds https://fitfoodiefinds.com/best-appetizers-for-a-healthy-game-day/

via Holistic Clients

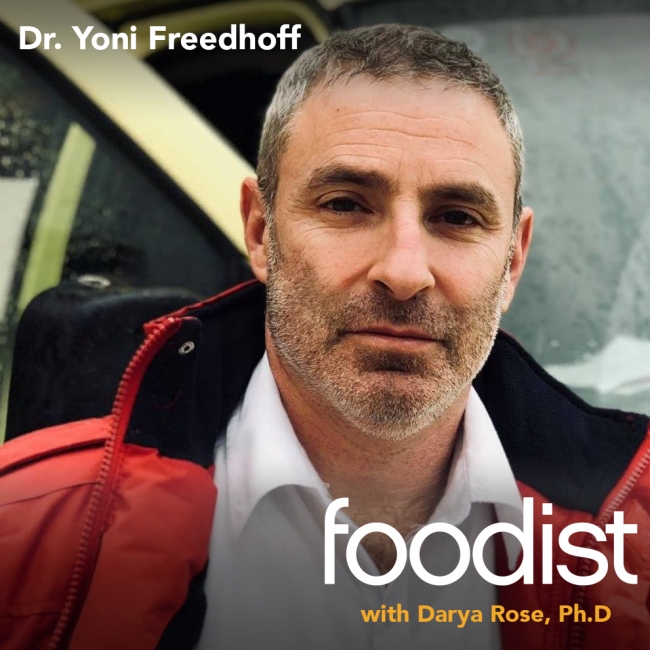

Dr. Yoni Freedhoff – Why you must like your life if you want to keep weight off

For humans, diets are not sustainable and food is more than just fuel. Today Yoni Freedhoff MD sits down with Darya to explain why the key to long-term weight management is enjoying your life.

Dr. Freedhoff is an Associate Professor of Family Medicine at the University of Ottawa and the medical director of Ottawa’s Bariatric Medical Institute. Widely regarding as Canada’s most outspoken expert in obesity Dr. Freedhoff’s advocacy work has seen him testifying in front of both the House of Commons and the Senate, as a subject in the acclaimed Canadian documentary Sugar Coated, and as something of a fixture in both National and International media regarding nutrition, public policy, and obesity. Dr. Freedhoff’s award winning blog Weighty Matters has received over 19,000,000 visits and his book The Diet Fix: Why Diets Fail and How to Make Yours Work is a #1 National Canadian bestseller.

Listen:

from Summer Tomato https://www.summertomato.com/dr-yoni-freedhoff-why-you-must-like-your-life-if-you-want-to-keep-weight-off

via Holistic Clients

Easy Vegan Minestrone Soup

[[ This is a content summary only. Visit my website for full links, other content, and more! ]]

from Running on Real Food https://runningonrealfood.com/easy-vegan-minestrone-soup/

via Enlightened Marketing

9 Camping Hacks You Can’t Live Without!

Make your next camping trip a breeze with these 9 epic camping hacks! From eggs in a water bottle to our sleeping bag heater trick, we’ve got some simple ways for you to have the best camping trip ever. Hello friends! We are so excited to be partnering with our ...

Make your next camping trip a breeze with these 9 epic camping hacks! From eggs in a water bottle to our sleeping bag heater trick, we’ve got some simple ways for you to have the best camping trip ever. Hello friends! We are so excited to be partnering with our ...

The post 9 Camping Hacks You Can’t Live Without! appeared first on Fit Foodie Finds.

from Fit Foodie Finds https://fitfoodiefinds.com/9-camping-hacks-you-cant-live-without/

via Holistic Clients

Thursday, 27 September 2018

We the Future: Talks from TED, Skoll Foundation and United Nations Foundation

Bruno Giussani (left) and Chris Anderson co-host “We the Future,” a day of talks presented by TED, the Skoll Foundation and the United Nations Foundation, at the TED World Theater in New York City, September 25, 2018. (Photo: Ryan Lash / TED)

We live in contentious times. Yet behind the dismaying headlines and social-media-fueled quarrels, people around the world — millions of them — are working unrelentingly to solve problems big and small, dreaming up new ways to expand the possible and build a better world.

At “We the Future,” a day of talks at the TED World Theater presented in collaboration with the Skoll Foundation and the United Nations Foundation, 13 speakers and two performers explored some of our most difficult collective challenges — as well as emerging solutions and strategies for building bridges and dialogue.

Updates on the Sustainable Development Goals. Are we delivering on the promises of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the collection of 17 global goals set by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015, which promised to improve the lives of billions with no one left behind? Using the Social Progress Index, a measure of the quality of life in countries throughout the world, economist Michael Green shares a fresh analysis of where we are today in relationship to the goals — and some new thinking on what we need to do differently to achieve them. While we’ve seen progress in some parts of the world on goals related to hunger and healthy living, the world is projected to fall short of achieving the ambitious targets set by the SDGs for 2030, according to Green’s analysis. If current trends keep up — especially the declines we’re seeing in things like personal rights and inclusiveness across the world — we actually won’t hit the 2030 targets until 2094. So what can we do about this? Two things, says Green: We need to call out rich countries that are falling short, and we need to look further into the data and find opportunities to progress faster. Because progress is happening, and we’re tantalizingly close to a world where nobody dies of things like hunger and malaria. “If we can focus our efforts, mobilize the resources, galvanize the political will,” Green says, “that step change is possible.”

Sustainability expert Johan Rockström debuts the Earth-3 model, a new way to track both the Sustainable Development Goals and the health of the planet at the same time. He speaks at “We the Future.” (Ryan Lash / TED)

A quest for planetary balance. In 2015, we saw two fantastic global breakthroughs for humanity, says sustainability expert Johan Rockström — the SDGs and the Paris Agreement. But are the two compatible, and can be they be pursued at the same time? Rockström suggests there are inherent contradictions between the two that could lead to irreversible planetary instability. Along with a team of scientists, he created a way to combine the SDGs within the nine planetary boundaries (things like ocean acidification and ozone depletion); it’s a completely new model of possibility — the Earth-3 model — to track trends and simulate future change. Right now, we’re not delivering on our promises to future generations, he says, but the window of success is still open. “We need some radical thinking,” Rockström says. “We can build a safe and just world: we just have to really, really get on with it.”

Henrietta Fore, executive director of UNICEF, is spearheading a new global initiative, Generation Unlimited, which aims to ensure every young person is in school, training or employment by 2030. She speaks at “We the Future.” (Photo: Ryan Lash / TED)

A plan to empower Generation Unlimited. There are 1.8 billion young people between the ages of 10 and 24 in the world, one of the largest cohorts in human history. Meeting their needs is a big challenge — but it’s also a big opportunity, says the executive director of UNICEF, Henrietta Fore. Among the challenges facing this generation are a lack of access to education and job opportunities, exposure to violence and, for young girls, the threats of discrimination, child marriage and early pregnancy. To begin addressing these issues, Fore is spearheading UNICEF’s new initiative, Generation Unlimited, which aims to ensure every young person is in school, learning, training or employment by 2030. She talks about a program in Argentina that connects rural students in remote areas with secondary school teachers, both in person and online; an initiative in South Africa called Techno Girls that gives young women from disadvantaged backgrounds job-shadowing opportunities in the STEM fields; and, in Bangladesh, training for tens of thousands of young people in trades like carpentry, motorcycle repair and mobile-phone servicing. The next step? To take these ideas and scale them up, which is why UNICEF is casting a wide net — asking individuals, communities, governments, businesses, nonprofits and beyond to find a way to help out. “A massive generation of young people is about to inherit our world,” Fore says, “and it’s our duty to leave a legacy of hope for them — but also with them.”

Improving higher education in Africa. There’s a teaching and learning crisis unfolding across Africa, says Patrick Awuah, founder and president of Ashesi University. Though the continent has scaled up access to higher education, there’s been no improvement in quality or effectiveness of that education. “The way we teach is wrong for today. It is even more wrong for tomorrow, given the challenges before us,” Awuah says. So how can we change higher education for the better? Awuah suggests establishing multidisciplinary curricula that emphasize critical thinking and ethics, while also allowing for in-depth expertise. He also suggests collaboration between universities in Africa — and tapping into online learning programs. “A productive workforce, living in societies managed by ethical and effective leaders, would be good not only for Africa but for the world,” Awuah says.

Ayọ (right) and Marvin Dolly fill the theater with a mix of reggae, R&B and folk sounds at “We the Future.” (Photo: Ryan Lash / TED)

Songs of hardship and joy. During two musical interludes, singer-songwriter Ayọ and guitarist Marvin Dolly fill the TED World Theater with the soulful, eclectic strumming of four songs — “Boom Boom,” “What’s This All About,” “Life Is Real” and “Help Is Coming” — blending reggae, R&B and folk sounds.

If every life counts, then count every life. To some, numbers are boring. But data advocate Claire Melamed says numbers are, in fact, “an issue of power and of justice.” The lives and death of millions of people worldwide happen outside the official record, Melamed says, and this lack of information leads to big problems. Without death records, for instance, it’s nearly impossible to detect epidemics until it’s too late. If we are to save lives in disease-prone regions, we must know where and when to deliver medicine — and how much. Today, technology enables us to inexpensively gather reliable data, but tech isn’t a cure-all: governments may try to keep oppressed or underserved populations invisible, or the people themselves may not trust the authorities collecting the data. But data custodians can fix this problem by building organizations, institutions and communities that can build trust. “If every life counts, we should count every life,” Melamed says.

How will the US respond to the rise of China? To Harvard University political scientist Graham Allison, recent skirmishes between the US and China over trade and defense are yet another chapter unfolding in a centuries-long pattern. He’s coined the term “Thucydides’ Trap” to describe it — as he puts it, the Trap “is the dangerous dynamic that occurs when a rising power threatens to displace a ruling power.” Thucydides is viewed by many as the father of history; he chronicled the Peloponnesian Wars between a rising Athens and a ruling Sparta in the 4th century BCE (non-spoiler alert: Sparta won, but at a high price). Allison and colleagues reviewed the last 500 years and found Thucydides’ Trap 16 times — and 12 of them ended in war. Turning to present day, he notes that while the 20th century was dominated by the US, China has risen far and fast in the 21st. By 2024, for instance, China’s GDP is expected to be one-and-a-half times greater than America’s. What’s more, both countries are led by men who are determined to be on top. “Are Americans and Chinese going to let the forces of history draw us into a war that would be catastrophic to both?” Allison asks. To avoid it, he calls for “a combination of imagination, common sense and courage” to come up with solutions — referencing the Marshall Plan, the World Bank and United Nations as fresh approaches toward prosperity and peace that arose after the ravages of war. After the talk, TED curator Bruno Giussani asks Allison if he has any creative ideas to sidestep the Trap. “A long peace,” Allison says, turning again to Athens and Sparta for inspiration: during their wars, the two agreed at one point to a 30-year peace, a pause in their conflict so each could tend to their domestic affairs.

Can we ever hope to reverse climate change? Researcher and strategist Chad Frischmann introduces the idea of “drawdown” — the point at which we remove more greenhouse gases from the atmosphere than we put in — as our only hope of averting climate disaster. At his think tank, he’s working to identify strategies to achieve drawdown, like increased use of renewable energy, better family planning and the intelligent disposal of HFC refrigerants, among others. But the things that will make the biggest impact, he says, are changes to food production and agriculture. The decisions we make every day about the food we grow, buy and eat are perhaps the most important contributions we could make to reversing global warming. Another focus area: better land management and rejuvenating forests and wetlands, which would expand and create carbon sinks that sequester carbon. When we move to fix global warming, we will “shift the way we do business from a system that is inherently exploitative and extractive to a ‘new normal’ that is by nature restorative and regenerative,” Frischmann says.

The end of energy poverty. Nearly two billion people worldwide lack access to modern financial services like credit cards and bank accounts — making it difficult to do things like start a new business, build a nest egg, or make a home improvement like adding solar panels. Entrepreneur Lesley Marincola is working on this issue with an interesting payment technology called Angaza that helps people avoid the steep upfront costs of buying a solar-power system, instead allowing them to pay it off over time.With metering technology embedded in the product, Angaza uses alternative credit scoring methods to determine a borrower’s risk level. The combination of metering technology and an alternative method of assessing credit brings purchasing power to unbanked people. “To effectively tackle poverty at a global scale, we must not solely focus on increasing the amount of money that people earn,” Marincola says. “We must also increase or expand the power of their income through access to savings and credit.”

Anushka Ratnayake displays one of the scratch-off cards that her company, MyAgro, is using to help farmers in Africa break cycles of poverty and enter the cycle of investment and growth. She speaks at “We the Future.” (Photo: Ryan Lash / TED)

An innovative way to help rural farmers save. While working for a microfinance company in Kenya, Anushka Ratnayake realized something big: small-scale farmers were constantly being offered loans … when what they really wanted was a safe place to save money. Collecting and storing small deposits from farmers was too difficult and expensive for banks, and research from the University of California, Berkeley shows that only 14–21 percent of farmers accept credit offers. Ratnayake found a simpler solution — using scratch-off cards that act as a layaway system. MyAgro, a nonprofit social enterprise that Ratnayake founded and leads, helps farmers save money for seeds. Farmers buy myAgro scratch cards from local stores, depositing their money into a layaway account by texting in the card’s scratch-off code. After a few months of buying the cards and saving little by little, myAgro delivers the fertilizer, seed and training they’ve paid for, directly to their farms. Following a wildly successful pilot program in Mali, MyAgro has expanded to Rwanda and Tanzania and now serves more than 50,000 farmers. On this plan, rural farmers can break cycles of poverty, Ratnayake says, and instead, enter the cycle of investment and growth.

Durable housing for a resilient future. Around the world, natural disasters destroy thousands of lives and erase decades of economic gains each year. These outcomes are undeniably devastating and completely preventable, says mason Elizabeth Hausler — and substandard housing is to blame. It’s estimated that one-third of the world will be living in insufficiently constructed buildings by 2030; Hausler hopes to cut those projections with a building revolution. She shares six straightforward principles to approach the problem of substandard housing: teach people how to build, use local architecture, give homeowners power, provide access to financing, prevent disasters and use technology to scale. “It’s time we treat unsafe housing as the global epidemic that it is,” Hausler says. “It’s time to strengthen every building just like we would vaccinate every child in a public health emergency.”

A daring idea to reduce income inequality. Every newborn should enter the world with at least $25,000 in the bank. That is the basic premise of a “baby trust,” an idea conceived by economists Darrick Hamilton of The New School and William Darity of Duke University. Since 1980, inequality has been on the rise worldwide, and Hamilton says it will keep growing due to this simple fact: “It is wealth that begets more wealth.” Policymakers and the public have fallen for a few appealing but inaccurate narratives about wealth creation — that grit, education or a booming economy can move people up the ladder — and we’ve disparaged the poor for not using these forces to rise, Hamilton says. Instead, what if we gave a boost up the ladder? A baby trust would give an infant money at birth — anywhere from $500 for those born into the richest families to $60,000 for the poorest, with an average endowment of $25,000. The accounts would be managed by the government, at a guaranteed interest rate of 2 percent a year. When a child reaches adulthood, they could withdraw it for an “asset-producing activity,” such as going to college, buying a home or starting a business. If we were to implement it in the US today, a baby trust program would cost around $100 billion a year; that’s only 2 percent of annual federal expenditures and a fraction of the $500 billion that the government now spends on subsidies and credits that favor the wealthy, Hamilton says. “Inequality is primarily a structural problem, not a behavioral one,” he says, so it needs to be attacked with solutions that will change the existing structures of wealth.

Nothing about us, without us. In 2013, activist Sana Mustafa and her family were forcibly evacuated from their homes and lives as a result of the Syrian civil war. While adjusting to her new reality as a refugee, and beginning to advocate for refugee rights, Mustafa found that events aimed at finding solutions weren’t including the refugees in the conversation. Alongside a group of others who had to flee their homes because of war and disaster, Mustafa founded The Network for Refugee Voices (TNRV), an initiative that amplifies the voices of refugees in policy dialogues. TNRV has worked with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and other organizations to ensure that refugees are represented in important conversations about them. Including refugees in the planning process is a win-win, Mustafa says, creating more effective relief programs and giving refugees a say in shaping their lives.

Former member of Danish Parliament Özlem Cekic has a novel prescription for fighting prejudice: take your haters out for coffee. She speaks at “We the Future.” (Photo: Ryan Lash / TED)

Conversations with people who send hate mail. Özlem Cekic‘s email inbox has been full of hate mail and personal abuse for years. She began receiving the derogatory messages in 2007, soon after she won a seat in the Danish Parliament — becoming one of the first women with a minority background to do so. At first she just deleted the emails, dismissing them as the work of the ignorant or fanatic. The situation escalated in 2010 when a neo-Nazi began to harass Cekic and her family, prompting a friend to make an unexpected suggestion: reach out to the hate mail writers and invite them out to coffee. This was the beginning of what Cekic calls “dialogue coffee”: face-to-face meetings where she sits down with people who have sent hate mail, in an effort to understand the source of their hatred. Cekic has had hundreds of encounters since 2010 — always in the writer’s home, and she always brings food — and has made some important realizations along the way. Cekic now recognizes that people of all political convictions can be caught demonizing those with different views. And she has a challenge for us all: before the end of the year, reach out to someone you demonize — who you disagree with politically or think you won’t have anything in common with — and invite them out to coffee. Don’t give up if the person refuses at first, she says: sometimes it has taken nearly a year for her to arrange a meeting. “Trenches have been dug between people, yes,” Cekic says. “But we all have the ability to build the bridges that cross the trenches.”

from TED Blog https://blog.ted.com/we-the-future-talks-from-ted-skoll-foundation-and-united-nations-foundation/

via Sol Danmeri

Bean-Free Chili Recipe (Paleo & Keto Friendly)

This fast bean-free chili recipe is a simple and filling meal on a cool day. It can be made as spicy (or not) as you like and even kids will gobble it up. We try to avoid the lectins in beans, so I make my chili bean-free. Give it a try, and let me know...

Continue reading Bean-Free Chili Recipe (Paleo & Keto Friendly)...

from Wellness Mama® https://wellnessmama.com/1827/bean-free-chili/

via SEO Derby

Do Your Kids Need to Eat Meat to Thrive?

Because of the prevailing idea in our culture that vegetarian and vegan diets are healthy, more and more kids are being raised from birth (or even conception!) without meat on their plates. If you’re considering a plant-based diet for your family, read on. Here’s my take on why kids need to eat meat to grow into healthy adults.

Is a Plant-Based Diet Safe for Your Children?

Both the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) and the USDA have stated that vegetarian and vegan diets are safe during pregnancy, but critical analyses by several researchers have questioned whether these recommendations are based on sufficient evidence.

Even though vegetarian and vegan diets have a reputation for being “healthy,” there are consequences to choosing a meat-free diet for your family. Find out why your kids need to eat meat to thrive.

One review remarked that “the evidence on vegan–vegetarian diets in pregnancy is heterogeneous and scant,” suggesting that more research is needed to answer the question of whether they are, in fact, safe during pregnancy. (1)

On meat-free diets for children, another review stated that “the existing data do not allow us to draw firm conclusions on health benefits or risks of present-day vegetarian type diets on the nutritional or health status of children and adolescents.” (2)

The limited studies on meat-free diets in children have severe shortcomings, including:

- Comparing meat-free diets to the typical unhealthy Standard American Diet (SAD), which is far from healthy

- Healthy-user bias (those who choose meat-free diets are also more likely to engage in “healthier” behaviors like exercising regularly, not smoking, etc.)

- Upper-class bias (higher-income families are more likely to choose meat-free diets and, in general, have better health)

- Small sample sizes

- Inaccuracies in diet reporting, which is a huge problem in nutrition research

Your Kids Need Nutrient-Dense Foods to Thrive

I know—it can be a struggle to get your kids to eat the “right” foods. With the processed junk that passes as “kid’s food” today, it’s even more difficult to ensure that your child eats a healthy diet. Research shows that the more restrictive the diet in children, the greater the risk for nutrient deficiencies. (6) When meat, which is one of the most nutrient-dense foods available, isn’t part of a child’s diet, these risks are even greater. Meat-free diets are unavoidably low in nutrient density, by favoring whole grains and legumes over animal products, making it harder for kids to get adequate nutrition. (7)

B12 Deficiency

The prevalence of B12 deficiency is 67 percent in American children, 50 percent in New Zealand children, and 85 percent in Norwegian infants who have followed vegetarian or vegan diets their entire lives. (8)

Studies have shown that kids raised until age 6 or 7 on a vegan diet are still B12 deficient years after adding at least some animal products to their diet (9). These children demonstrated persistent cognitive deficits 5 to 10 years after switching to a lactovegetarian or omnivorous diet.

One study found an association between B12 status and measures of intelligence and memory, with formerly vegan kids scoring lower than omnivorous kids. (10) Devastating case studies have reported B12 deficiency in young vegan children that have led to neurological damage and developmental delays. (11, 12, 13)

Vitamin D Deficiency

Vitamin D is virtually absent from vegan diets and often severely lacking in vegetarian diets. Along with calcium, magnesium, and vitamin K2, vitamin D is critical for proper bone growth and remodeling, especially during infancy and childhood. During the first year of life, human bone mass nearly doubles. (14) Massive bone growth occurs from birth to adulthood, during which a child will grow from approximately 20 inches to 60 or 70 inches or more. Even with adequate calcium intake, bone turnover markers were lower in child vegetarians compared to omnivores, increasing the risks of impaired bone growth and lower peak bone mass during adolescence. (15, 16)

Hypothyroidism

Low nutrient intake extends beyond vitamin B12 and D. Other case studies have attributed hypothyroidism in young children to a maternal and/or childhood vegan diet, possibly due to insufficient iodine. (17, 18)

DHA and EPA

Compared to breast milk from omnivorous mothers, breast milk from vegan mothers had lower levels of DHA and EPA, which are vital for brain development, especially in the first year of life, when a baby’s brain literally doubles in size. (19)

Iron Deficiency

Iron is already the most common nutritional deficiency in children. Because meat-free diets require at least 1.8 times the iron intake due to lower iron availability in plant foods, iron deficiency is more common in vegetarian and vegan children than in omnivores. (20, 21, 22, 23) Children on vegetarian and vegan diets also can have lower intakes of vitamin A and zinc. (24, 25)

Your Kids Need to Eat Meat—Not Supplements

Can you just give your meat-free kid a multivitamin and call it a day? Unfortunately, probably not. Research indicates that regular supplementation with iron, zinc, and B12 does not mitigate all of the serious developmental risks in fetuses and children. (26) Nutrient-dense whole foods, like meat, are the best sources for vitamins and minerals.

Now I’d like to hear from you. Are you considering a vegetarian or vegan diet for your child, or do you believe that kids need to eat meat? Let me know below in the comment section!

The post Do Your Kids Need to Eat Meat to Thrive? appeared first on Chris Kresser.

from Chris Kresser https://chriskresser.com/do-your-kids-need-to-eat-meat-to-thrive/

via Holistic Clients

What Is the Optimal Human Diet?

Eggs are bad for you. Wait, eggs are good for you! Fat is bad. Wait, fat is good and carbs are bad! Skipping breakfast causes weight gain. Wait, skipping breakfast (intermittent fasting) is great for weight loss and metabolic health.

It’s enough to make you crazy, right? These are just a few of the many contradictory nutrition claims that have been made in the media over the past decade, and it’s no wonder people are more confused about what to eat than ever before.

Everyone has an opinion on the optimal human diet—from your personal trainer to your UPS driver, from your nutritionist to your doctor—and they’re all convinced they are right. Even the “experts” disagree. And they can all point to at least some studies that support their view. On the surface, at least, all of these studies seem credible, since they’re published in peer-reviewed journals and come out of respected institutions like Harvard Public Health.

This has led to massive confusion among both the general public and health professionals, a proliferation of diet books and fad approaches, and a (justifiably) growing mistrust in public health recommendations and media reporting on nutrition.

Unfortunately, millions of dollars and decades of scientific research haven’t added clarity—if anything, they have further muddied the waters. Why? Because, as you’ll learn below, we’ve been asking the wrong questions, and we’re using the wrong methods.

If you’re confused about what to eat and frustrated by the contradictory headlines that are constantly popping up in your news feed, you’re not alone. The current state of nutritional research, and how the media reports on it, virtually guarantees confusion.

In this article, my goal is to step back and look at the question of what we should eat through a variety of lenses, including archaeology, anthropology, evolutionary biology, anatomy and physiology, and biochemistry—rather than relying exclusively on observational nutrition research, which, as I’ll explain below, is highly problematic (and that’s saying it nicely).

Armed with this information, you’ll be able to make more informed choices about what you eat and what you feed your family members.

Let’s start with the question that is on everyone’s mind ...

What Is the Optimal Human Diet?

Drumroll, please!

There isn’t one.

Note the emphasis on “one.”

When I explain this to people I talk to, they immediately understand. It makes sense to them that we shouldn’t all be following the exact same diet.

Yet that is exactly what public health recommendations and dietary guidelines assume, and I would argue that this fallacy is both the greatest source of confusion and the most significant obstacle to answering our key questions about nutrition.

Why? Because although human beings share a lot in common, we’re also different in many ways: we have different genes, gene expression, health status, activity levels, life circumstances, and goals.

Modern dieting advice is often confusing, contradictory, and just plain wrong. And, while there’s no such thing as one optimal human diet, there are some foods humans are designed to eat. Find out what should be on your plate—from a Paleo perspective.

Imagine two different people:

- A 55-year-old, sedentary male office worker who is 60 pounds Overweight and has pre-diabetes and hypertension

- A 23-year-old, female Olympic athlete who is training for three hours a day, in fantastic health, and is attempting to build muscle for a competition

Should they eat exactly the same diet? Of course not.

Our Differences Matter When It Comes to Diet

Although that may be an extreme example, it’s no less true that what works for a young, single, male, CrossFit enthusiast who is getting plenty of sleep and not under a lot of stress won’t work for a mother of three who also works outside the house and is burning the candle at both ends.

These differences—in our genes, behavior, lifestyle, gut microbiome, etc.—influence how we process both macronutrients (protein, carbohydrates, and fat) and micronutrients (vitamins, minerals, and trace minerals), which in turn determine our response to various foods and dietary approaches. For example:

- People with lactase persistence—a genetic adaptation that allows them to digest lactose, the sugar in milk, into adulthood—are likely to respond better to dairy products than people that don’t have this adaptation.

- Populations with historically high starch intake produce more salivary amylase than populations with low starch intake. (1)

- Changes to gut microbiota can help with the assimilation of certain nutrients. Studies of Japanese people have found, for example, that their gut bacteria produce specific enzymes that help them break down seaweed, which can be otherwise difficult for humans to digest. (2)

- Organ meats and shellfish are extremely nutrient dense and a great choice for most people—but not for someone with hemochromatosis, a genetic disorder that leads to aggressive iron storage, since these foods are so rich in iron.

- Large, well-controlled studies (involving up to 350,000 participants) have found that, on average, higher intakes of saturated fat are not associated with a higher risk of heart disease. (3) But is this true for people with certain genes that make them “hyper-absorbers” of saturated fat and lead to a significant increase in LDL particle number (a marker associated with greater risk of cardiovascular disease)?

This is just a partial list, but it’s enough to make the key point: there are important differences that determine what an optimal diet is for each of us, but those differences are rarely explored in nutrition studies. Most research on diet is almost exclusively focused on top-down, population-level recommendations, and since a given dietary approach will yield variable results among different people, this keeps us stuck in confusion and controversy.

It has also kept us stuck in what Gyorgy Scrinis has called “the ideology of nutritionism,” which he defines as follows: (4)

Nutritionism is the reductive approach of understanding food only in terms of nutrients, food components, or biomarkers—like saturated fats, calories, glycemic index—abstracted out of the context of foods, diets, and bodily processes.

In other words, it is a focus on quantity, not quality.

Nutrition research has assumed that a carbohydrate is a carbohydrate, a fat is a fat, and a protein is a protein, no matter what type of food they come packaged in. If one person eats 50 percent of calories from fat in the form of donuts, pizza, candy, and fast food and another person eats 50 percent of calories from fat in the form of whole foods like meat, fish, avocados, nuts, and seeds, they will still be lumped together in the same “50 percent of calories from fat” group in most studies.

Most people are shocked to learn that this is how nutrition research works. It doesn’t take a trained scientist to understand why this would be problematic.

But Aren’t There Some Foods That Are Better for All Humans to Eat (And Not Eat)?

I just finished explaining why there’s no “one-size-fits-all” approach to diet, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t core nutrition principles that apply to everyone.

For example, I think we can all agree that a steady diet of donuts, chips, candy, soda, and other highly processed and refined foods is unhealthy. And most people would agree that a diet based on whole, unprocessed foods is healthy.

It’s the middle ground where we get into trouble. Is meat good or bad? If it’s bad, does that apply to all meats, or just processed meat or red meat? What about saturated fat? Should humans consume dairy products?

A better question than “What is the optimal human diet?” then, might be “What is a natural human diet?” or, more specifically, “What is the range of foods that human beings are biochemically, physiologically, and genetically adapted to eat?”

In theory, there are two ways to answer this question:

- We can look at evolutionary biology, archaeology, medical anthropology, and comparative anatomy and physiology to determine what a natural human diet is.

- We can look at it from a biochemical perspective: what essential and nonessential nutrients contribute to human health (and where are they found in foods), how various functional components of food influence our body at the cellular and molecular level, and how certain compounds in foods—especially those prevalent in the modern, industrialized diet—damage our health via inflammation, disruption of the gut microbiome, hormone imbalance, and other mechanisms.

Let’s take a closer look through each of these lenses.

The Evolutionary Perspective

Human beings, like all other organisms in nature, evolved in a particular environment, and that evolutionary process dictated our biology and physiology as well as our nutritional needs.

Archaeological Evidence for Meat Consumption

Isotope analysis from archaeological studies suggests that our hominid ancestors have been eating meat for at least 2.5 million years. (5) There is also wide agreement that going even further back in time, our primate ancestors likely ate a diet similar to modern chimps, which we now know eat vertebrates. (6) The fact that chimpanzees and other primates evolved complex behavior like using tools and hunting in packs indicates the importance of animal foods in their diet—and ours.

Anatomical Evidence for Meat Consumption

The structure and function of the digestive tract of all animals can tell us a lot about their diet, and the same is true for humans. The greatest portion (45 percent) of the total gut volume of our primate relatives is the large intestine, which is good for breaking down fiber, seeds, and other hard-to-digest plant foods. In humans, the greatest portion of our gut volume (56 percent) is the small intestine, which suggests we’re adapted to eating more bioavailable and energy-dense foods, like meat and cooked starches, that are easier to digest.

Some advocates of plant-based diets have argued that humans are herbivores because of our blunt nails, small mouth opening, flat incisors and molars, and relatively dull canine teeth—all of which are characteristics of herbivorous animals. But this argument ignores the fact that we evolved complex methods of procuring and processing food, from hunting to cooking to using sharp tools to rip and tear flesh. These methods/tools take the place of anatomical features that serve the same function.

Humans have relatively large brains and small guts compared to our primate relatives. Most researchers believe that consuming meat and fish is what led to our larger brains and smaller guts compared to other primates because animal foods are more energy dense and easier to digest than plant foods. (7)

Genetic Changes Suggestive of Adaptation to Animal Foods

Most mammals stop producing lactase, the enzyme that breaks down lactose, the sugar in milk, after they’re weaned. But in about one-third of humans worldwide, lactase production persists into adulthood. This allows those humans to obtain nutrients and calories from dairy products without becoming ill. If we were truly herbivores that aren’t supposed to eat animal foods at all, we would not have developed this genetic adaptation.

Studies of Contemporary Hunter–Gatherers

Studies of contemporary hunter–gatherer populations like the Maasai, Inuit, Kitavans, Tukisenta, !Kung, Aché, Tsimané, and Hadza have shown that, without exception, they consume both animal and plant foods, and they go to great lengths to obtain plant or animal foods when they’re in short supply.

For example, in one analysis of field studies of 229 hunter–gatherer groups, researchers found that animal food provided the dominant source of calories (68 percent) compared to gathered plant foods (32 percent). (8) Only 14 percent of these societies got more than 50 percent of their calories from plant foods.

Another report on 13 field studies of the last remaining hunter–gatherer tribes carried out in the early and mid-20th century found similar results: animal food comprised 65 percent of total calories on average, compared with 35 percent from plant foods. (9)

The amount of protein, fat, and carbohydrates, the proportion of animals vs. plants, and the macronutrient ratios consumed vary, but an ancestral population following a completely vegetarian or vegan diet has never been discovered.

The Lifespan of Our Paleolithic Ancestors

Critics of Paleo or ancestral diets often claim that they are irrelevant because our Paleolithic ancestors all died at a young age. This common myth has been debunked by anthropologists. (10) While average lifespan is and was lower among hunter–gatherers than ours is today, this is heavily skewed by high rates of infant mortality (due to a lack of emergency medical care and other factors) in these populations.

The anthropologists Gurven and Kaplan studied lifespan in extant hunter–gatherers and found that, if they survive childhood, their lifespans are roughly equivalent to our own in the industrialized world: 68 to 78 years. (11) This is notable because hunter–gatherers today survive only in isolated and marginal environments like the:

- Kalahari Desert

- Amazon rainforest

- Arctic circle

What’s more, in many cases hunter–gatherers reach these ages without acquiring the chronic diseases that are so common in Western countries. They’re less likely to have heart disease, diabetes, dementia and Alzheimer’s, and many other debilitating, chronic conditions.

For example, one study of the Tsimané people in Bolivia found that they have a prevalence of atherosclerosis 80 percent lower than ours in the United States and that nine in 10 Tsimané adults aged 40 to 94 had completely clean arteries and no risk of heart disease. (12) They also found that the average 80-year-old Tsimané male had the same vascular age as an American in his mid-50s. (Did you notice that this study included adults up to age 94? So much for the idea that hunter–gatherers all die when they’re 30!)

When you put all of this evidence together, it suggests the following themes:

- Meat and other animal products have been part of the natural human diet for at least 2.5 million years

- All ancestral human populations that have been studied ate both plants and animals

- Human beings can survive on a wide variety of foods and macronutrient ratios within the general template of plants and animals they consumed

Additional Reading

For a deeper dive on this topic, I recommend the following articles:

- The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 1: Evolution & Hunter–Gatherers

- The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 2: Physiological & Biological Evidence

- Hunter–gatherers enjoy long, healthy lives

- Eating meat led to smaller stomachs, bigger brains

The Biochemical Perspective

Understanding ancestral diets and their relationship to the health of hunter–gatherer populations is a good starting place, but on its own, it doesn’t prove that such diets are the best option for modern humans.

To know that, we need to examine this question from a biochemical perspective. We need to know what nutrients are essential to human health, where they are found in food, and how various components of the diet and compounds in foods affect our physiology—both positively and negatively.

The good news is, there are tens of thousands of studies in this category. Collectively, they bring us to the same conclusion we reached above:

Nutrient Density

Nutrient density is arguably the most important concept to understand when it comes to answering the question, “What should humans eat?”

The human body requires approximately 40 different micronutrients for normal metabolic function.

There are two types of nutrients in food: macronutrients and micronutrients. Macronutrients refer to the three food substances required in large amounts in the human diet, namely:

- Protein

- Carbohydrates

- Fats

Micronutrients, on the other hand, are vitamins, minerals, and other compounds required by the body in small amounts for normal physiological function.

The term “nutrient density” refers to the concentration of micronutrients and amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, in a given food. While carbohydrates and fats are important, they can be provided by the body for a limited amount of time when dietary intake is insufficient (except for the essential omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids). On the other hand, micronutrients and the essential amino acids found in protein cannot be manufactured by the body and must be consumed in the diet.

With this in mind, what are the most nutrient-dense foods? There are several studies that have attempted to answer this question. In the most comprehensive one, which I’ll call the Maillot study, researchers looked at seven major food groups and 25 subgroups, characterizing the nutrient density of these foods based on the presence of 23 qualifying nutrients. (13)

Maillot and colleagues found that the most nutrient-dense foods were (score in parentheses):

- Organ meats (754)

- Shellfish (643)

- Fatty fish (622)

- Lean fish (375)

- Vegetables (352)

- Eggs (212)

- Poultry (168)

- Legumes (156)

- Red meats (147)

- Milk (138)

- Fruits (134)

- Nuts (120)

As you can see, eight of the 12 most nutrient-dense categories of foods are animal foods. All types of meat and fish, vegetables, fruit, nuts, and dairy were more nutrient-dense than whole grains, which received a score of only 83. Meat and fish, veggies, and fruit were more nutrient dense than legumes, which were slightly more nutrient dense than dairy and nuts.

There are a few caveats to the Maillot analysis:

- It penalized foods for being high in saturated fat and calories

- It did not consider bioavailability

- It only considered essential nutrients

Caloric Density and Saturated Fat

In the conventional perspective, nutrient-dense foods are defined as those that are high in nutrients but relatively low in calories. However, recent evidence (which I’ll review below) has found that saturated fat doesn’t deserve its bad reputation and can be part of a healthy diet. Likewise, some foods that are high in calories (like red meat or full-fat dairy) are rich in key nutrients, and, again, can be beneficial when part of a whole-foods diet. Had saturated fat and calories not been penalized, foods like red meat, eggs, dairy products, and nuts and seeds would have appeared even higher on the list.

Bioavailability

Bioavailability is a crucial factor that is rarely considered in studies on nutrient density. It refers to the portion of a nutrient that is absorbed in the digestive tract. The amount of bioavailable nutrients in a food is almost always lower than the amount of nutrients the food contains. For example, the bioavailability of calcium from spinach is only 5 percent. (14) Of the 115 mg of calcium present in a serving of spinach, only 6 mg is absorbed. This means you’d have to consume 16 cups of spinach to get the same amount of bioavailable calcium in one glass of milk!

The bioavailability of protein is another essential component of nutrient density. Researchers use a measure called the Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS), which combines the amino acid profile of a protein with a measure of how much of the protein is absorbed during digestion to assess protein bioavailability. The PDCAAS rates proteins on a scale of 0 to 1, with values close to 1 representing more complete and better-absorbed proteins than ones with lower scores.

On the scale, animal proteins have much higher scores than plant proteins; casein, egg, milk, whey, and chicken have scores of 1, indicating excellent amino acid profiles and high absorption, with turkey, fish, and beef close behind. Plant proteins, on the other hand, have much lower scores; legumes, on average, score around 0.70, rolled oats score 0.57, lentils and peanuts are 0.52, tree nuts are 0.42, and whole wheat is 0.42.

Thus, had bioavailability been considered in the Maillot study, animal foods would have scored even higher, and plant foods like legumes would have scored lower.

Essential vs. Nonessential Nutrients

The Maillot study—and a similar analysis from Harvard University chemist Dr. Mat LaLonde—only considered essential nutrients. In a nutritional context, the term “essential” doesn’t just mean “important,” it means necessary for life. We need to consume essential nutrients from the diet because our bodies can’t make them on their own.

Focusing on essential nutrients makes sense, since we can’t live without them. That said, over the past few decades many nonessential nutrients have been identified that are important to our health, even if they aren’t strictly essential. These include:

- Carotenoids

- Polyphenols

- Flavonoids

- Lignans

- Fiber

Many of these nonessential nutrients are found in fruits and vegetables. Had these nutrients been included in the nutrient density analyses, fruits and vegetables would likely have scored higher than they did.

What Can We Conclude from the Biochemical Perspective?

But how much of the diet should come from animals, and how much from plants? The answer to this question will vary based on individual needs. If we look at evolutionary history, we see that on average, humans obtained about 65 percent of calories from animal foods and 35 percent of calories from plant foods on average, but the specific ratios varied depending on geography and other factors.

That does not mean that two-thirds of what you put on your plate should be animal foods! Remember, calories are not the same as volume (what you put on your plate). Meat and animal products are much more calorie-dense than plant foods. One cup of broccoli contains just 30 calories, compared to 338 calories for a cup of beef steak.

This means that even if you’re aiming for 50 to 70 percent of calories from animal foods, plant foods will typically take up between two-thirds and three-quarters of the space on your plate.

(Side note: this is why I’ve always rejected the notion of Paleo as an “all-meat” diet; a more accurate descriptor would be a plant-based diet that also contains animal products).

When we consider the importance of both essential and nonessential nutrients, it also becomes clear that both plant and animal foods play an important role because they are rich in different nutrients. Dr. Sarah Ballantyne broke this down in part three of her series “The Diet We’re Meant to Eat: How Much Meat versus Veggies.”

Plant Foods

- Vitamin C

- Carotenoids (lycopene, beta-carotene, lutein, zeaxanthin)

- Diallyl sulfide (from the allium class of vegetables)

- Polyphenols

- Flavonoids (anthocyanins, flavan-3-ols, flavonols, proanthocyanidins, procyanidins, kaempferol, myricetin, quercetin, flavanones)

- Dithiolethiones

- Lignans

- Plant sterols and stanols

- Isothiocyanates and indoles

- Prebiotic fibers (soluble and insoluble)

Animal Foods

- Vitamin B12

- Heme iron

- Zinc

- Preformed vitamin A (retinol)

- High-quality protein

- Creatine

- Taurine

- Carnitine

- Selenium

- Vitamin K2

- Vitamin D

- DHA (docosahexaenoic acid)

- EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid)

- CLA (conjugated linoleic acid)

Additional Reading

For a deeper dive on these subjects, check out the following articles:

- What Is Nutrient Density and Why Is It Important?

- The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 3: How Much Meat versus Veggies

Focus Your Diet on Nutrient Density

Whether we look through the lens of evolutionary biology and history or modern biochemistry, we arrive at the same conclusion:

Anthropology and archaeology suggest that it’s possible for humans to thrive on a variety of food combinations and macronutrient ratios within the basic template of whole, unprocessed animal and plant foods.

For example, the Tukisenta of Papua New Guinea consumed almost 97 percent of calories in the form of sweet potatoes, and the traditional Okinawans also had a very high intake of carbohydrate and low intake of animal protein and fat. On the other hand, cultures like the Maasai and Inuit consumed a much higher percentage of calories from animal protein and fat, especially at certain times of year.

How much animal vs. plant food you consume should depend on your specific preferences, needs, and goals. For most people, a middle ground is what appears to work best, with between 35 and 50 percent of calories from animal foods and between 50 and 65 percent of calories coming from plant foods. (Remember, we’re talking about calories, not volume.)

Now I’d like to hear from you. What is your “optimal human diet”? Have you experimented with different ratios of animal vs. plant foods? What works for you? Let me know in the comments section.

The post What Is the Optimal Human Diet? appeared first on Chris Kresser.

from Chris Kresser https://chriskresser.com/what-is-the-optimal-human-diet/

via Holistic Clients

Why You Should Be Skeptical of the Latest Nutrition Headlines: Part 2

This article is Part 2 of a two-part series about the problems with nutrition research and the way it’s presented in the media. For more reasons why you should be skeptical of the latest nutrition headlines, check out Part 1 of this series.

In my last article in this series, I talked about why observational studies aren’t a great tool for proving causal relationships; how the data collection methods researchers use rely on memory, not facts; how the healthy-user bias can impact study results; and how, in many cases, nutritional studies uncover “risks” that look an awful lot like pure chance. In this post, I’ll delve deeper into the reasons why you should take nutrition headlines with a grain of salt.

Some Scientific Results Can’t Be Replicated

Science works by experiments that can be repeated; when they are repeated, they must give the same answer. If an experiment does not replicate, something has gone wrong. – Young & Karr, The Royal Statistical Society (1)

As Young and Karr suggest above, replication is a key feature of the scientific method. An initial finding does not carry much weight on its own. For it to be considered valid, it needs to be replicated by other researchers.

We’re supposed to trust nutrition researchers to help us understand our health, but in some cases, the way they think about nutrition is faulty. Check out more reasons why you should remain skeptical of nutrition headlines.

In the context of nutrition research, because observational studies cannot prove causality, their findings should ideally be replicated in a randomized controlled trial

(RCT). RCTs are specifically designed to prove causality, and while not perfect (see below), they are much more persuasive as evidence than observational studies.

The results from most observational nutrition studies have not been replicated by RCTs. In fact, one analysis found that:

Yes, you read that correctly. Out of 52 claims made in observational nutrition studies, zero were replicated and five indicated the opposite of what the observational study suggested!

Let’s look at a specific example. Observational studies suggested that people with the highest intakes of beta-carotene, an antioxidant nutrient found primarily in fruits and vegetables, had a 31 percent lower risk of death compared to those with the lowest intake. Yet RCTs of supplementation with beta-carotene not only failed to confirm this benefit, they found an increased risk of cancer in the group with the highest intake. (2) Oops! Similar results have been found with vitamin E. (3)

Researchers Focus on Quantity, Not Quality

People don’t eat nutrition, they eat food. – Margaret Mead

The vast majority of observational studies today focus only on nutrients, isolated food components, or biomarkers—like saturated fats, carbohydrates, calories, LDL cholesterol—abstracted out of the context of foods, diets, and bodily processes.

The upside of nutritionism has been the discovery of drugs, vitamins, and minerals that have saved millions of lives. The downside is that Americans (and people all over the industrialized world) are obsessing over details like the percentage of fat or carbohydrates they consume rather than focusing on the broader and more important issues, like the quality of the food they eat.

Two examples of how this has manifested over the past few decades are:

- The promotion of margarine over the much better-tasting butter because of concerns about butter’s saturated fat content

- The vilification of eggs due to their cholesterol content without considering their overall nutrient value

(And of course, we now know that butter is healthier than margarine and dietary cholesterol has no impact on heart disease. Another oops!)

Nutritionism is a relatively new phenomenon. It started in 1977 with the McGovern Report, the first widely disseminated nutrition guidance to provide detailed, quantitative, nutrient-focused dietary recommendations. (5) Prior to that, dietary guidelines were based on familiar concepts of food groups and serving sizes and relatively simple information on what foods to buy and eat to maintain health. The average person could easily understand—and most importantly, act on—the guidelines.

After the McGovern Report, dietary guidelines became increasingly complex and difficult for the layperson to comprehend. The 1980 dietary guidelines were published in a short, 19-page brochure; in 1985 it grew to 28 pages; in 2010 it was 112 pages; and in 2015, the most recent dietary guidelines took up 517 pages!

What Happens When You Look at Food Quality

A more recent example of nutritionism can be found in the heated debate over whether low-fat or low-carb diets are superior for weight loss and metabolic and cardiovascular health. Each side of the debate has its advocates, and the controversy continues.

In early 2018, a group of researchers led by Dr. Christopher Gardner set out to settle this debate with an RCT. They assigned participants into two groups: low-carb and low-fat. But here’s the catch: they instructed both groups to:

1) maximize vegetable intake; 2) minimize intake of added sugars, refined flours, and trans fats; and 3) focus on whole foods that were minimally processed, nutrient dense, and prepared at home whenever possible. (6)

For example, foods like fruit juice, pastries, white rice, white bread, and soft drinks are low in fat but were not recommended to the low-fat group. Instead, the dietitians encouraged participants to eat whole foods like lean meat, brown rice, lentils, low-fat dairy products, legumes, and fruit. Meanwhile, the low-carb group was instructed to focus on foods rich in healthy fats, like olive oil, avocados, salmon, cheese, nut butters, and pasture-raised animal products.

Perhaps not surprisingly—if you don’t embrace nutritionism, that is—the researchers found that on average, people who cut back on added sugar, refined grains, and processed food lost weight over 12 months—regardless of whether the diet was low-carb or low-fat.

This was a fantastic example of what a nutrition study should look like. It resulted in clinically relevant, practical advice that is easy for people to follow: eat real food. Just imagine where we might be now if most nutrition studies over the past 40 years had been designed like this?

RCTs Are Better than Observational Studies but Still Problematic

If observational studies cannot prove causality, then why do they continue to form the foundation of dietary guidelines and public health recommendations? The answer is that RCTs also have several shortcomings that, thus far, have made them impractical as a tool for studying population health.

Duration

Most relationships between nutritional factors and disease can take years, if not decades, to develop. What’s more, the effects of some nutritional interventions in the short term are different than they are over the long term.

Weight loss is a great example. Both low-carb and low-fat diets have been shown to cause weight loss in the short term, but over the long term (more than 12 months) people tend to regain the weight they lost.

Inadequate Sample Size

The sample size, or number of participants in an RCT, is one of the most important factors in determining whether the results of the study are generalizable to the wider population. Most nutrition RCTs do not have a large enough sample size.

Dr. John Ioannidis, a professor at the Stanford School of Medicine, highlighted this problem in a recent editorial in BMJ called “Implausible Results in Human Nutrition Research.”

To identify a nutrition-related intervention that produces a legitimate 5 to 10 percent relative risk reduction in total mortality, we’d need studies that are 10 times as large as the highly publicized PREDIMED trial (which had around 7,500 participants), in addition to long-term follow-up, linkage to death registries, and careful efforts to maximize adherence.

RCTs Are Expensive

One reason that it’s such a huge challenge to design RCTs with sufficient duration and sample size is cost. RCTs are enormously expensive. In the pharmaceutical world, drug companies pay for RCTs because they have a vested financial interest in their results. But who will pay for long-term RCTs in the nutrition world? Public funding for nutrition research (and many other types of research) is declining, not increasing, which makes it unlikely that we’ll see long-term RCTs with sufficient sample sizes anytime soon.

Quality RCTs Are Difficult to Do

As Dr. Peter Attia points out in his excellent series Studying Studies, designing high-quality RCTs is fraught with challenges:

These trials need to establish falsifiable hypotheses and clear objectives, proper selection of endpoints, appropriate subject selection criteria (both inclusionary and exclusionary), clinically relevant and feasible intervention regimens, adequate randomization, stratification, and blinding, sufficient sample size and power, and anticipation of common practical problems that can be encountered over the course of an RCT.

That’s not an easy task and few nutrition RCTs meet the challenge.

Conflicts of Interest Are Very Common

It’s difficult to get a man to understand a thing if his salary is dependent upon him not understanding it. – Upton Sinclair

Many have written about financial conflicts of interest and their impact on all forms of research, including nutrition research. In short, research has shown that when studies are funded by industry, they are far more likely to report results that are favorable to the sponsor.

In one analysis performed by Marion Nestle, 90 percent of industry-sponsored studies returned sponsor-friendly results. (7) For a summary of the issues and how they impact the quality of nutrition research, I recommend this story from Vox.

In this article, I’d like to focus on another type of conflict of interest: allegiance bias, which is also known as “white hat bias.” Allegiance bias is not as well recognized as financial conflicts of interest are, which is one of the many reasons that it has an insidious effect on nutrition research.

For example, imagine that a vegan researcher sets out to do a study on the health impacts of a vegan diet. Is it possible that the researcher’s ideological commitment to veganism could influence, both consciously and unconsciously, how the study is designed, executed, and interpreted? Of course it could. In fact, it’s difficult to see how it couldn’t.

In a 2018 editorial called “Disclosures in Nutrition Research: Why It Is Different,” Dr. Ioannidis suggests that allegiance bias should be disclosed by researchers, just as financial conflicts of interest are. He says:

Therefore, it is important for nutrition researchers to disclose their advocacy or activist work as well as their dietary preferences if any are relevant to what is being presented and discussed in their articles. This is even more important for dietary preferences that are specific, circumscribed, and adhered to strongly. [emphasis added]

Ioannidis goes on to say that advocacy and activism, while laudable, are contrary to “a key aspect of the scientific method, which is to not take sides preemptively or based on belief or partisanship.” [emphasis added]

Veganism certainly meets the criteria of dietary recommendations that are “specific, circumscribed, and adhered to strongly.” In fact, some have pointed out that veganism meets the four dimensions of religion:

- Belief: Veganism began as a way to express moral integrity regarding the appropriation and suffering of non-humans.

- Ritual: Veganism involves strict dietary restrictions, including abstaining from the use of materials made from any animal products.

- Experience: The “holistic connectedness” of veganism would be considered a religious experience to those who live it.

- Community: There are many official and unofficial vegan associations across the world, and in 2017 a civil flag was created for the international vegan community.

Researchers and physicians like T. Colin Campbell, Kim Williams, Caldwell Esselstyn, Joel Fuhrman, John McDougall, and Neal Barnard could all be expected to suffer from this “white hat bias.” They’re involved in vegan advocacy and activism, both of which could be expected to be a source of allegiance bias.

A Famous Example of Allegiance Bias at Work

The China Study, a book by vegan physician and researcher T. Colin Campbell, is a perfect example. Campbell claimed that this study—which was not peer-reviewed—proved that:

- Animal protein causes cancer

- A plant-based diet protects against heart disease

- You can get all the nutrients you need from plants

Campbell even went as far as saying, “Eating foods that contain any cholesterol above 0 mg is unhealthy,” a claim that has been completely disproven and is reflected in the 2015 change in the U.S. Dietary Guidelines that no longer regards dietary cholesterol as a nutrient of concern.

However, since The China Study was published, several independent, peer-reviewed studies of the data have refuted T. Colin Campbell’s claims. For a great summary of the issues with The China Study, see this article by nutritional scientist Dr. Chris Masterjohn.

Allegiance bias can take several forms. It can involve:

- Cherry-picking studies to support a cherished view

- Misleadingly describing the results of studies that are cited in a paper

- “Data dredging” to search for statistical significance within given data sets (when no such significance is present)

- Not reporting null results

- Designing experiments for the purpose of obtaining a particular answer

- And more

Nutrition Policy Is Informed by Politics and Religion—Not Just Science

In a perfect world, dietary guidelines and nutritional policy would be the product of a thorough and dispassionate review of the available scientific evidence and not be unduly influenced by politics—and certainly not by religion. Dissenting views that are well informed would be not only welcomed but encouraged. As Syd Shapiro once said, “We should never forget that good science is skeptical science.”

Alas, we don’t live in a perfect world. In our world, dissenting views are are not welcomed; they’re suppressed. Dr. D. Mark Hegsted, a founding member of the Nutrition Department at the Harvard School of Public Health, made this opening remark in the 1977 McGovern hearing:

The diet of Americans has become increasingly rich—rich in meat, other sources of saturated fat and cholesterol … [and] the proportion of the total diet contributed by fatty and cholesterol-rich foods … has risen.

The only problem with this statement is that it directly contradicted USDA economic data which suggested that total calories and the availability of meat, dairy, and eggs at the time of the report were equivalent or marginally less than amount consumed in 1909. Full-fat dairy consumption was lower in 1977 than 1909, having declined steadily from 1950 to 1977. (9) Other evidence that contradicted Dr. Hegsted’s opinion was also ignored.

The feedback from the scientific community on the McGovern Report was “vigorous and constructive,” explicitly stated the “lack of consensus among nutrition scientists,” and presented evidence for the diversity of scientific opinion on the subject. (10) Other countries, such as Canada and Great Britain, also noted the lack of consensus on whether dietary cholesterol intake should be limited. U.S. senators issued the following statement about the McGovern Report:

It is clear that science has not progressed to the point where we can recommend to the general public that cholesterol intake be limited to a specified amount. The variances between different individuals are simply too great. A similar divergence of scientific opinion on the question of whether dietary change can help the heart illustrates that science cannot yet verify with any certainty that coronary heart disease will be prevented or delayed by the diet recommended in this report. (See footnote)

Nevertheless, these cautionary words were ignored, and the recommendations from the McGovern Report were adopted. This kicked off the fat and cholesterol phobia that would grip the United States for the next four decades.

Religion Can Impact Nutrition Guidelines

Another example of how non-scientific factors drive nutrition policy is the influence of the Seventh Day Adventists on public health recommendations in the United States and around the world. Seventh Day Adventists (SDA) is a Protestant denomination that grew out of the Millerite movement in the United States. Health has been a focus of SDA teachings since the inception of the church in the 1860s. According to Wikipedia:

Adventists are known for presenting a “health message” that advocates vegetarianism and expects adherence to the kosher laws, particularly the kosher foods described in Leviticus 11, meaning abstinence from pork, shellfish, and other animals proscribed as “unclean.” The church discourages its members from consuming alcoholic beverages, tobacco or illegal drugs. ... In addition, some Adventists avoid coffee, tea, cola, and other beverages containing caffeine.

Ellen White, an early SDA church leader, received her first major health reform vision in 1863, and “for the first time, God’s people were urged to abstain from flesh food in general and from swine’s flesh in particular.” Most SDA diet beliefs are based on White’s health visions.

White believed that the church had a duty to educate the public about health as a way to control desires and passions. Adventists continue to believe that eating meat stirs up “animal passions,” and that is one of the reasons for avoiding it.

Another early SDA leader, Lenna Cooper, was a dietitian who cofounded the American Dietetics Association, which continues to advocate a vegetarian diet to this day. Cooper wrote textbooks and other materials that were used in dietetic and nursing programs, not only in the United States but around the world, for more than 30 years. The SDA Church established hundreds of hospitals, colleges, and secondary schools and tens of thousands of churches around the world—all promoting a vegetarian diet—and played a major role in the development and mass production of plant-based foods, such as meat analogues, breakfast cereals, and soy milk. (11)

Adventists have been behind much of the early research on vegetarian diets at Loma Linda University in San Diego, where SDA leaders established a dietetics department in 1908. This was an ostensibly scientific endeavor at a university that was established by a religious group that believed vegetarianism was ordained by God.

If you think this raises a huge red flag for allegiance bias, you’re not wrong. In fact, as Jim Banta pointed out in a fascinating review of the SDA influence on diet, administrators at Loma Linda University in the mid-1900s initially discouraged research on vegetarian diets because “if you find the diets of vegetarians are deficient, it will embarrass us.” That is not the attitude of skepticism and open-minded inquiry that characterizes good science.

My Final Thoughts on Nutrition Research

I’d like to conclude with the opening two paragraphs of a recent open letter that scientists Edward Archer and Chip J. Lavie wrote to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine:

“Nutrition” is now a degenerating research paradigm in which scientifically illiterate methods, meaningless data, and consensus-driven censorship dominate the empirical landscape. Since the 1950s, there was a naïve but politically expedient consensus that a person’s usual diet could be measured simply by asking what he or she remembered eating and drinking. Despite the credulous and unfalsifiable nature of this memory-based method, investigators used it to produce hundreds of thousands of publications and acquire billions of taxpayer dollars.