As Lili finished her workout, it felt like everyone was staring at her.

Because they were.

It took her longer to complete the group session than everyone else, and the coach made a point of having the whole class stick around and encourage her.

Afterward, the coach and classmates approached Lili to say: “It’s really great that you’re exercising. Good for you.”

She understood everyone was trying to be inclusive and nice. But, deep down, Lili also knew she was being singled out for her 300-pound frame. It made her feel incredibly self-conscious.

So she never went back.

Ranjan had a similar experience. He struggled with binge eating, and felt ashamed when his coach said, “It’s not that hard to avoid fast food,” and “Unless you’re about to run a marathon, there’s no reason to ever eat a bagel.”

He quit two weeks into a 12-week group diet challenge—even though he’d already paid in full.

Angele ghosted her coach, too, after months of great progress.

She’d originally signed up to feel stronger and more in control of her body. And though her trainer knew weight loss wasn’t her goal, his compliment about how fit she looked was met with a blank stare.

Turns out, Angele was struggling with the trauma of an assault that happened years before. Comments about her body were majorly triggering.

These coaching scenarios? They’re all inspired by real client stories.

The coaches who made these mistakes never knew what went wrong. Or how much pain they’d inadvertently caused.

But the underlying reason for each is the same:

Many health and fitness professionals tend to focus too much on weight loss and body size.

If reading that made you feel like putting your fist through the screen, hear us out: We’re not suggesting that helping clients lose weight is wrong.

Many of your clients WILL absolutely want to lose weight, for various reasons.

But there’s a difference between helping clients who come to you for weight loss and assuming all clients want to lose weight.

This is especially important to understand if you work with clients in larger bodies—many of whom may not want to lose weight right now, or ever.

Here’s the most important thing to know: Regardless of whether a client wants to lose weight or not, the way you talk about weight, body image, and fat loss can make or break the coach-client relationship.

It affects how freely clients share information—and ultimately whether they’re able to succeed.

This is particularly true with clients who:

- have trauma and/or negative feelings around their body or weight

- are in a body that doesn’t fit the norm of what their culture considers “fit and healthy.”

(FYI: It’s pretty likely that many of your clients will fall into one, if not both, of these categories.)

In this article you’ll find:

- 5 strategies for forming strong, lasting relationships with clients of all body sizes.

- Dozens of resources that can help you understand clients on a deeper, more personal level.

- What to say (and not say) to clients who are struggling with body image, guilt, and shame.

(Note: This article isn’t intended to “fix” complex issues like weight stigma. But it can help you avoid reinforcing harmful ideas about weight, weight loss, and what health truly means.)

+++

5 ways to respectfully support all clients—no matter what kind of body they’re in.

It’s not a coach’s job to tell a client how their body should be.

Here at Precision Nutrition, we believe all clients:

- Get to decide their own goals, whether that’s weight loss or anything else.

- Deserve to feel safe and supported sharing their goals and decisions with their coach, whatever those goals and decisions are.

- Benefit from being informed about ways they can improve their health—including options that have nothing to do with weight or size.

Okay, so what does that look like in practice?

We’ll show you.

Are we talking about body positivity here?

Sorta.

But also, not really.

Originally, the body positivity movement was a safe space for people in the most marginalized bodies—people who are treated as “other” for how their bodies looked.

These days, you might associate the term “body positive” with Instagram photos of people highlighting their cellulite, stretch marks, and stomach rolls.

Ironically, these types of posts have become especially popular among people in relatively fit, conventionally-attractive bodies. In other words, the movement has been co-opted by the mainstream.

That’s why some of today’s activists, particularly ones within the nutrition and fitness world, use terms like body liberation, body neutrality, and anti-diet instead.

If you want to learn more about weight stigma/bias movements like Health at Every Size, how fatphobia is intertwined with other “isms” like racism or ableism, and other related topics, you’ll find boxes throughout this article that provide further resources to explore.

#1: Give every client the blank slate treatment.

See if you can spot what goes wrong in this coach-client interaction.

Martha is a 48-year-old woman. She’s always lived in a larger body. In the past year, she’s struggled with chronic back pain. She thinks making some changes to her exercise and nutrition habits might help, so she contacts a coach she found on Facebook.

In the initial consultation, Martha introduces herself in her customarily lively, outgoing way. The coach says:

“I’m so glad you reached out to me. In your email, you mentioned you’re dealing with back pain. I think we can definitely make some changes that’ll help with that! How much weight do you want to lose? It’s so smart of you to be proactive about this!”

Martha’s utterly deflated. This coach won’t be hearing from her again.

Why? Two big problems:

- Martha never mentioned wanting to lose weight.

- She said she’s dealing with back pain, but that’s all the coach knows about Martha’s health.

What the coach in this scenario didn’t know was that Martha has struggled with her weight for what feels like her whole life. She’s often felt too big, too bulky, too awkward in her body.

Now in her late 40s, she’s starting to feel at peace with herself. After all, this body has been home for nearly five decades.

So when Martha hears what this coach has to say? She feels those old emotions creeping back. She’s frustrated, angry, and fed-up with people—like this young, genetically-predisposed-to-be-fit coach—assuming she can’t possibly be happy with her body.

This isn’t just a rookie coaching mistake, by the way. Experienced coaches do stuff like this, too.

Thanks to our cultural conditioning, many of us have hidden biases in this area. So it’s important to be conscious of not equating:

- weight with health

- desire to improve health, fitness, or food choices with weight loss

Because when you’re fine with your weight but someone assumes you’re not… or they imply you shouldn’t be… it stings.

Even the most confident people will likely feel a pang of, ‘Wait, is my body okay? Am I okay?!’ Or even: ‘I was right. This fitness stuff just isn’t for me.’

The takeaway: Don’t assume your clients want to lose weight.

Check your assumptions. Consider what you don’t know about your clients, and how you might learn more about them.

Wait for them to tell you what they want.

Otherwise, you risk damaging your relationship—and causing your client pain—before you even get started.

Why is fat activism a thing?

… and why should you care about it as a coach?

People in smaller bodies are often shocked to learn what life can be like for people in larger bodies.

For instance, one client in a larger body told us that if she appears to be buying “junk” food for herself at the grocery store, she braces herself for comments from the cashier, other people waiting in line, and even people passing her in the freezer aisle.

And those comments? They can range from “are you sure you want to buy that?” to “better not buy that ice cream, fatty.”

If you’re a straight-size person reading this—that is, a person who can walk into any store and find clothes that fit—you may be shocked to learn this ACTUALLY HAPPENS.

Imagine not being able to buy your stinking ice cream in peace. Now imagine that’s the least of the prejudice you experience on a daily basis. (Especially if you’re also white, cisgender, and heterosexual—so you’re really not used to it.)

And if you’re in a larger body—or ever have been—you might be thinking ‘Do people really not know this happens?!’

People in larger bodies are discriminated against all the freaking time. We know this from real-life experiences and research. For example, people in larger bodies are more likely to:

- Receive a lower standard of health care because their doctors are biased (either consciously or unconsciously) 1 2 3

- Get fewer preventative health services and screenings, which can mean not discovering life-threatening health problems in time 4 5

- Avoid making doctor appointments because they’re afraid of being judged or mistreated 6 7

- Be unfairly passed over for jobs, promotions, and educational opportunities 8 9

- Deal with mental health challenges, potentially related to discrimination. 10

These are just some of the disadvantages people in larger bodies experience. And for Black and brown people—especially women—they’re compounded by racism. This is particularly true in the area of health care. 11 12

These problems are part of why body positivity, fat activism, and other related movements exist.

But these movements are about more than helping people defend themselves from discrimination and stigma.

They’re also about helping people shift from feeling ashamed—and like they’ll never fit in—to feeling actively proud of their bodies.

Not in spite of being big. But because they’re big.

If fat activism’s existence doesn’t quite add up to you, consider this: What if no matter how you feel about yourself, society tells you there’s something wrong with your body and it’s all your fault? In this situation, reclaiming the narrative for yourself is one of the most powerful things you can do.

Learn more: Body positivity and fat activism

Learn more: Health at Every Size and the Anti-Diet movement

Health at Every Size and the anti-diet movement both reject the idea that purposeful weight loss is healthy, and that weight and BMI are reliable indicators of health.

Both communities advocate for only making changes to your diet, exercise routine, and lifestyle based on preference and quality of life improvements that aren’t related to weight.

#2. Dig deeper—even when a client’s goal is as simple as “I want to lose weight.”

About half of Americans say they want to lose weight, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 13 (And that trend is likely to translate to other similar cultures.)

There’s also this: Some clients say they want to lose weight simply because they feel that’s the only societally acceptable option for their body. Or because they’re living in a culture that tells them losing weight will automatically make them happier and healthier.

Plus, clients often have important secondary goals, in addition to weight loss. For instance, our Precision Nutrition Coaching clients are almost always interested in fat loss. But that’s not all they’re after.

On a 1 to 10 scale, clients commonly rank the following as a 9 or higher:

- looking and feeling better (81 percent), which may or may not have anything to do with weight loss

- developing consistency (75 percent)

- maintaining their healthy habits (74 percent)

- gaining energy and vitality (59 percent)

Over time, these goals may become more important than weight loss.

Talk with your clients to clarify their goals and motivations so:

- They understand that weight loss isn’t the only option available to them.

- You get the information you need to help your clients succeed.

The following strategies will help you do just that.

Present a variety of goals that are all treated as equally valid.

One way PN Master Coach Kate Solovieva normalizes all types of body goals: giving clients options.

For instance, whether she’s working with a 75-year-old woman or a 25-year-old man, Solovieva might ask: “What are you hoping to achieve through coaching? Do you want to gain weight, lose weight, feel stronger, move without pain, love how you look naked?”

By letting your clients know they have lots of different choices, they’re more likely to feel safe telling you what they really want. You might even open their eyes to the fact that weight loss isn’t their only way forward.

Ask this secret-weapon question.

Here’s a powerful coaching question for any client who wants to lose weight, courtesy of Precision Nutrition’s Director of Curriculum, Krista Scott Dixon, PhD:

“What else is going on for you right now?”

Just ask it, and let your client talk.

Why?

“Being ‘on a diet’ is an A+ way to avoid all the other crap in your life,” says Dr. Scott-Dixon. Sometimes when people realize they don’t have anything to fill the void, they decide going on a diet will help them feel better and more fulfilled.

Your client might reveal that they’re going through a divorce, dealing with a sick parent, or feeling unhappy in their job.

Losing weight won’t fix those problems.

This is why it’s a good idea to…

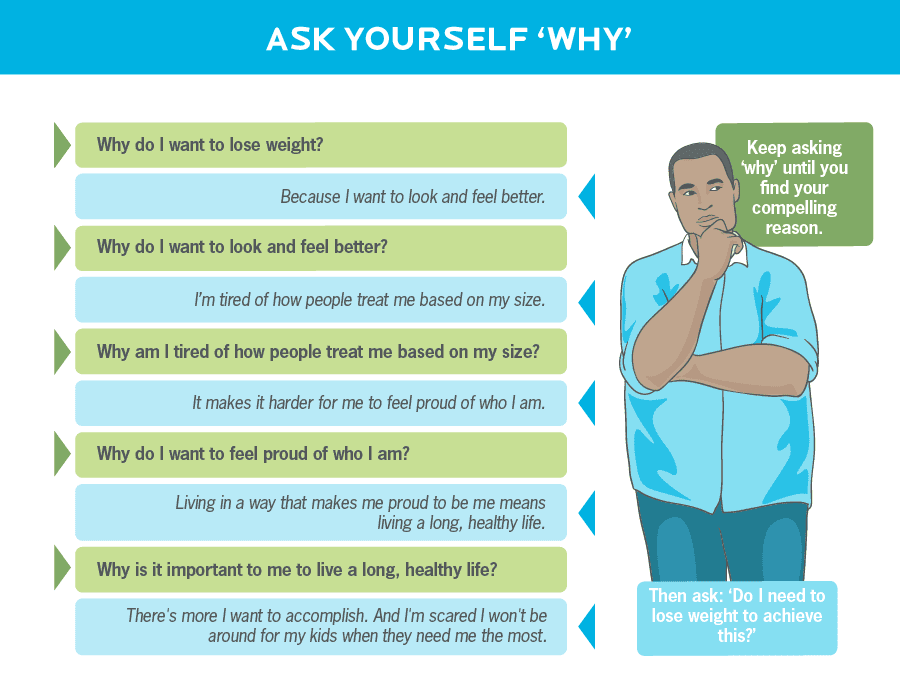

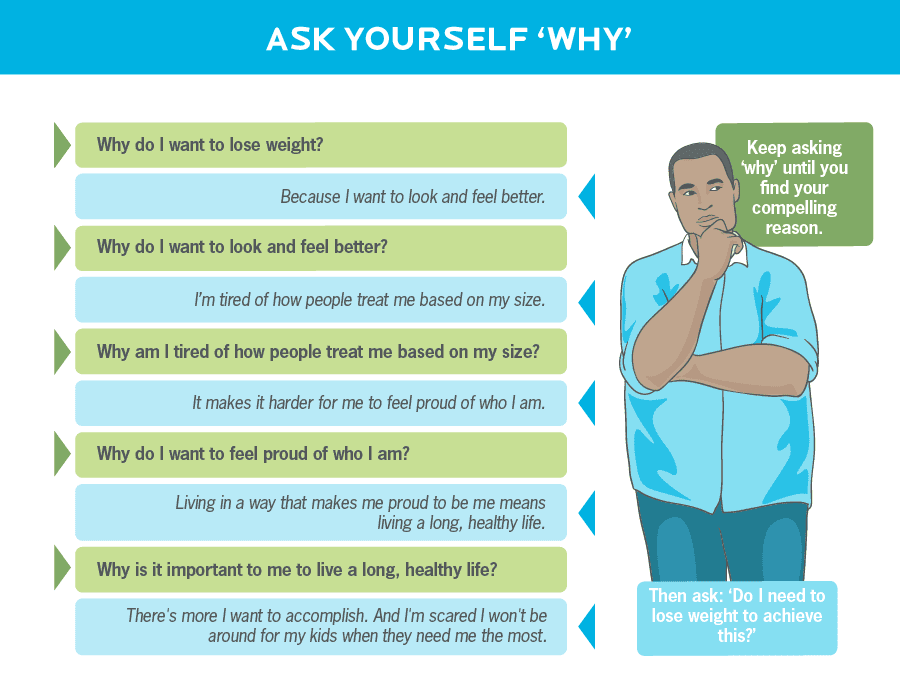

Always ask why.

We often use an exercise called The 5 Whys with our clients.

It starts with a simple question: “Why do I want to change my eating and exercise habits?”

Then, whatever answer your client comes up with, ask why again. And so on, five times, until you get to the heart of what’s really behind their goal.

You can use this worksheet to get started.

This exercise helps clients move past motivations that focus on comparing themselves to others.

Sometimes, when people can’t come up with a compelling deeper reason to lose weight, they realize weight loss might not be what they’re really after.

(And sometimes it IS weight loss. That’s okay, too.)

#3. Understand that body image exists on a spectrum.

“If you work with clients enough, you know that almost everyone has some kind of body angst. It doesn’t matter what shape they have,” says Dr. Scott-Dixon.

As a coach, you can help people develop more productive, deep-health promoting experiences of themselves in their bodies.

Why should you care? “We know objectively that the more you hate yourself, the worse your life is,” Dr. Scott-Dixon says.

Struggling with body image:

- Makes it harder to do well academically (especially for women), which can shut down future educational opportunities and chances at landing your dream job 14

- Increases the likelihood of disordered eating, as well as eating disorders like anorexia nervosa and bulimia, making anything related to food feel like an uphill battle 15 16

- May make you feel afraid to date or get romantic with someone. (Think: turning off the lights so they can’t see you, or never speaking up about your romantic feelings for someone out of fear of being rejected) 17

- Can lead to generally feeling like your life sucks (officially, this is called “poor quality of life”), along with having a difficult time going through the motions of daily life, including interacting with other people 18

- Means you’re less likely to work out or be active, maybe because the idea of going to the gym or moving your body feels super uncomfortable or intimidating 19

- Increases risk of depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem 20

Many people believe that criticizing themselves will help them excel at changing their habits and living better, healthier lives.

But constant self-criticism and being “down” on yourself can make it much, much harder to adopt healthy habits.

For example, clients in larger bodies who also struggle with body image sometimes tell us they don’t feel comfortable entering gyms and other fitness or wellness spaces. Often, it’s because they don’t feel these spaces are meant for people who look like them.

While it’s true some gyms aren’t particularly welcoming to people of all body sizes, improving body image can make finding a supportive fitness space and developing regular exercise habits feel much more manageable.

How to respond to body negativity

Chances are, you’ve heard a client say something like:

- “Ugh, I hate my fat legs!”

- “I really need to lose this belly fat. It’s disgusting.”

- “I hate my body right now.”

What can you possibly say to make someone feel better?

According to Precision Nutrition Super Coach Lisanne Thomas, the most impactful thing you can do is ask productive questions.

You might frame it like this:

“Can I ask you a question about that?”

If they say yes, proceed with something like…

“Imagine your best friend/partner/child just had that thought about themselves. How might you respond to them if they shared that thought with you?”

OR

“Imagine someone speaking to your loved one like that while in your presence. How might you show up for your friend/partner/child in support and response to those words?”

These questions can help people recognize just how unkind they’re being to themselves.

In a recent Facebook Live, Chrissy King, a writer, speaker, powerlifter, and strength and fitness coach shared her strategy for challenging what our bodies are “supposed” to look like.

When faced with a comment like, “My stomach rolls are so gross,” question what exactly makes them gross, and what standard you’re measuring against.

“This doesn’t come from a place of judgement or shame,” said King. “There are no right or wrong answers. It’s just that we’re taking the time to really think through it. When we really sit with our feelings, underlying a lot of these things aren’t our own personal beliefs. These are things we are taught. These are things that we see societally.”

So it may be worth asking:

- “What would it mean if you woke up tomorrow and didn’t have that roll on your stomach?”

- “What would change about your life?”

- “Would you be a better person?”

- “Would you be a happier person?”

People may find that their answers surprise them.

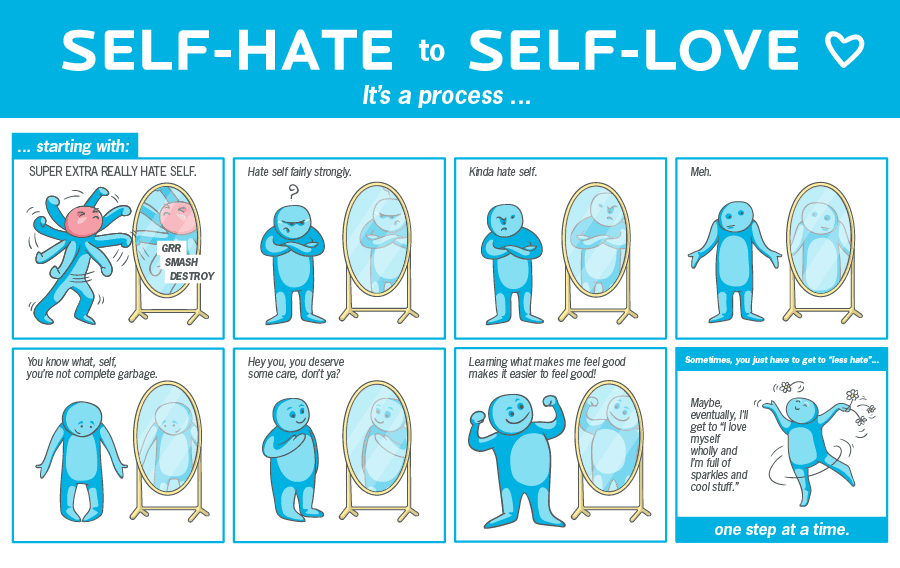

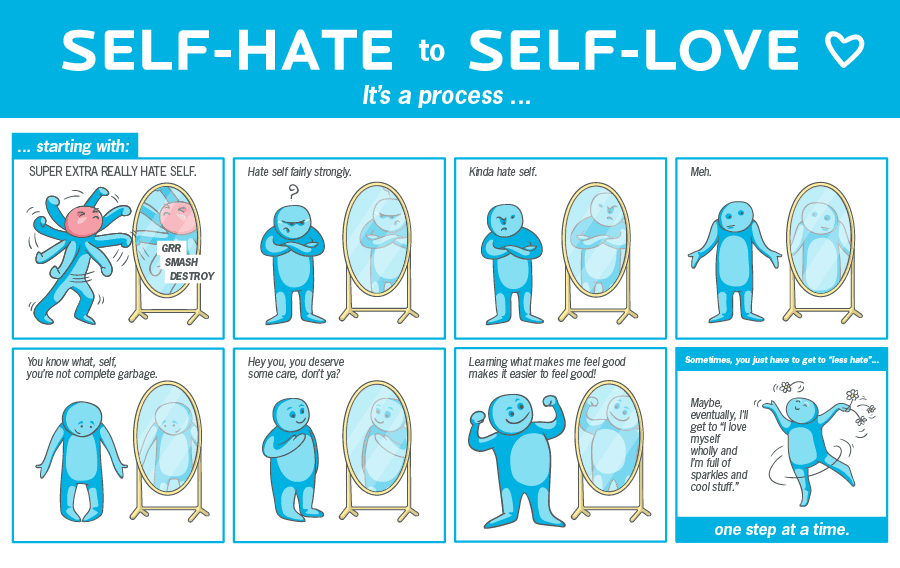

Of course, you can’t just snap your fingers and decide to love your body. So think about body image on a spectrum.

On one end: Body negativity, or actively disliking your body.

On the other end: self-love.

And body neutrality, or “meh,” as we like to refer to it? Somewhere in between.

Here’s the thing: We might exist on multiple parts of the spectrum at once. Human beings are complex, and body dissatisfaction and positive body image aren’t direct opposites of each other. 21

But the goal is to nudge ourselves up the continuum, so we’re spending more time in the body neutrality and self-love sections than before.

The bottom line: You can’t make a client love their body.

But you can refrain from adding more negativity to someone’s baggage.

And remember, complete body positivity and absolute self-love aren’t necessarily the goal.

“For many people, getting to ‘meh’ is actually a pretty good goal,” says Dr. Scott-Dixon.

Self-love resources

Precision Nutrition Super Coach Lisanne Thomas often talks about self-love with her clients. “My role as a coach is to help a client love and care for their body and do with it what they want,” she says.

While conversations about self-love can be helpful, sharing articles, videos, books, and more that “speak for themselves” may also help start a productive discussion, or just provide food for thought.

Below are some of Coach Lisanne’s favorite resources.

#4. Use language as a signal.

Here’s another coaching scenario to consider:

Your client tells you they ate a pint of ice cream last night.

What’s your gut reaction?

Think about it. Then read on.

As much as possible, avoid saying anything that might make your client feel ashamed, Solovieva recommends.

Beware of responses that sound supportive, but are actually criticism, like, “Oh, that’s a bummer. How’d you get so off track?” or even, “No worries! We all slip up from time to time.”

“Clients are always listening to see how you talk about things,” Solovieva says. It helps them determine how trustworthy you are with their most difficult feelings and behaviors.

This is important in many areas, but especially when it comes to food. That’s why, when faced with a client eating a late-night pint of ice cream, Solovieva starts with:

“What flavor was it?!”

She might follow it up with any number of questions, like “How are you feeling this morning?” or “Did you enjoy it?”

These kinds of open-ended, judgement-free questions help clients feel comfortable talking about what’s really going on in their heads.

Normalize all food choices.

People aren’t great at remembering or estimating what or how much they’ve eaten. 22 This is often what’s at play when clients say they’re not overeating (or undereating), but still aren’t seeing results.

But there could be another reason clients aren’t reporting their food intake accurately: They don’t feel safe doing so.

And this can be conscious OR unconscious.

Conscious: Your client chooses not tell you about their late-night pint of ice cream because they fear your response—and how it’ll make them feel.

Unconscious: They underestimate their food intake because they want to avoid being shamed for eating eight ounces (or thumbs) of cheese instead of the “acceptable” serving size of one.

In either case, it’s going to make it hard for you as a coach to see what’s really going on.

One way to normalize food choices, according to Solovieva: Openly talk about foods that people may believe are “off limits.” (Friendly reminder: There are no “bad” foods.)

For instance, you might ask:

“What do you normally eat for lunch at work? Is it more like a salad, or a sandwich, or tacos?”

When talking about food planning for the weekend, you might say:

“What are you having for dinner Saturday night? My family always has pizza!”

From there, you can still encourage clients to make their meals “a little bit better” by adding a side of veggies, or upping the protein content. But normalizing your client’s food choices helps you meet them where they’re at.

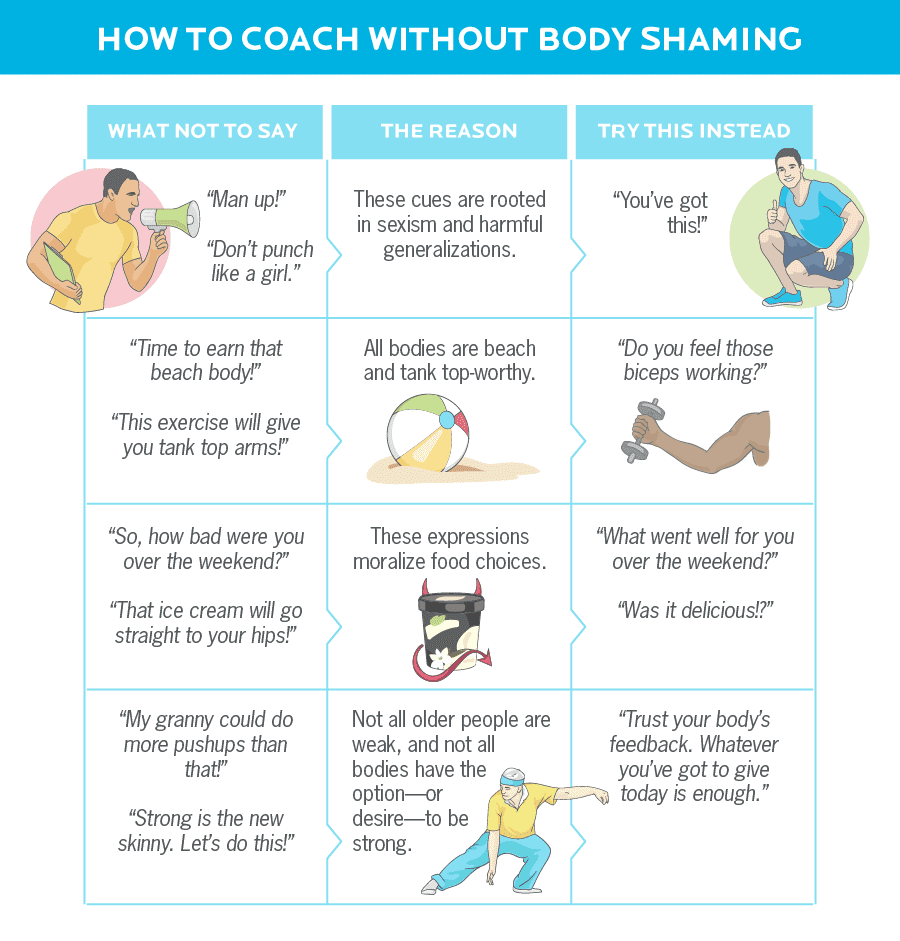

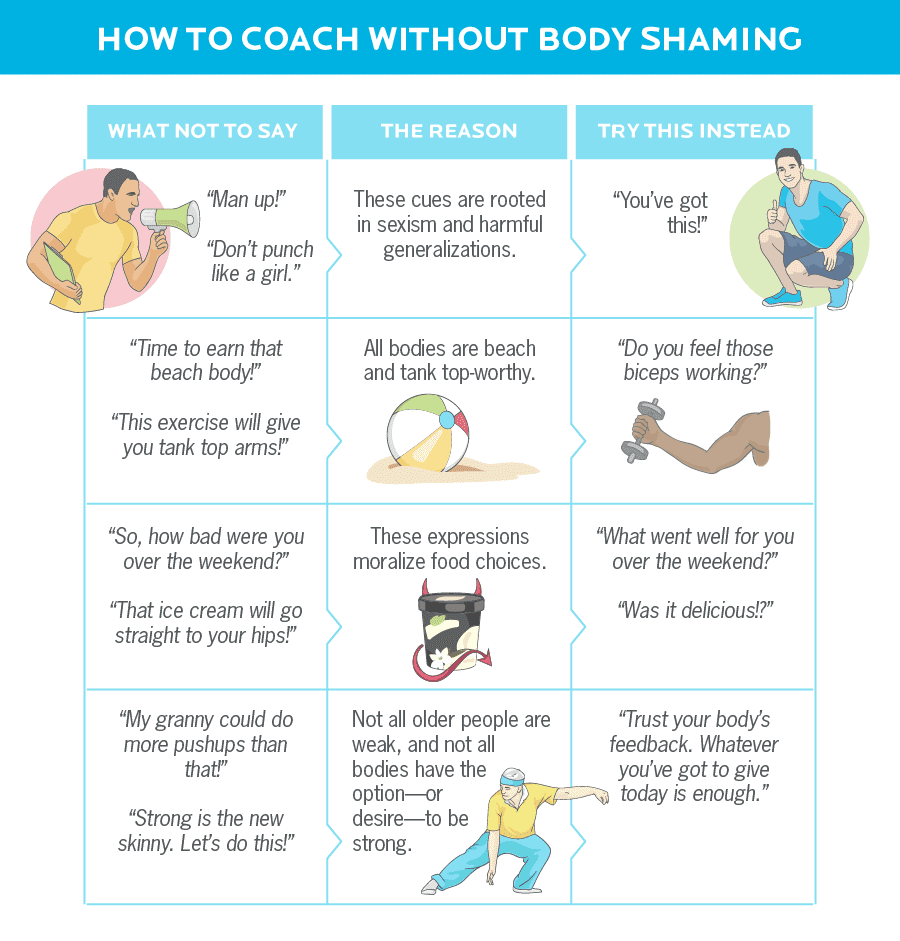

Skip body-shaming “motivational” language.

Many coaches don’t realize certain phrases and cues can make people feel “less than.”

Here are some ways coaches might unintentionally be signaling clients that there’s something wrong with their bodies, plus what to say instead.

(Note: Many of these cues have been commonly used for what feels like forever. So we’re not criticizing coaches for using them. We’re pointing out why evolving your language will ultimately help your clients—and your coaching.)

Model healthy, or at least neutral, body image.

You set an example for your clients. In many cases, they look to you for information about what it means to be healthy and fit.

So saying you’re going to “shred for summer” probably isn’t the best way to signal to your client that their post-baby body (or whatever kind of body) is completely fine.

We’re not saying you need to have it all figured out yourself.

In fact, it’s common for coaches to:

- feel shame about or have a complicated relationship with their own bodies

- feel like an imposter for not fitting into a certain body ideal

- worry they don’t look “good enough” to attract clients

- have gone through their own body transformation journey

- have experienced living in a bigger body themselves (whether currently or in the past)

Ironically, coaches who have been through their own process of coming to health and fitness after feeling ashamed about their bodies are often the best qualified to really understand what clients go through, Dr. Scott-Dixon points out. That’s a superpower in itself.

So if you’re comfortable, it may help to share your own body image journey with clients once you’ve gotten to know them.

Showing vulnerability lets clients know they’re not alone.

Plus, people are more likely to be open and honest about their challenges when they feel you can relate.

No matter where you are on the body negativity to self-love spectrum, be conscious of the language you use. This includes what you say around your clients, in your marketing materials, and in your social media posts.

That way, you can ensure you’re not passing any of your own body image struggles onto others—or reinforcing their existing ones.

#5. Be trustworthy.

Trust is a key element in the coach-client relationship.

Here’s the tricky part: “You can’t make clients trust you,” says Precision Nutrition Coach Jon Mills. “You have to be trustworthy.”

So how do you do that, exactly?

The art of coaching is about being trustworthy for ALL your clients, including those who:

- are in larger bodies

- have a disability or chronic illness

- identify as trans and/or non-binary

- are part of marginalized communities

- come from cultures different from your own

You might be thinking: “I don’t have any clients like that!” or “I don’t really cater to any of those groups.”

The truth is that you probably do—even if you don’t realize it.

Many disabilities and health issues, like ADHD and diabetes, can be completely invisible from the outside. You won’t necessarily know someone’s sexual orientation, gender identity, or race from looking at them.

And just because you don’t currently have clients who outwardly appear different from you in terms of body size, race, gender, or in any other aspect doesn’t mean you can’t coach those clients.

What coaches need to know about intersectionality

We can’t talk about weight stigma and bias without talking about race and intersectionality.

Intersectionality is a term coined by law professor Kimberlé Crenshaw. It refers to how social and political categorizations like race, class, and gender interconnect to create both discrimination and privilege. 23

Crenshaw pointed out that when it came to discrimination, the legal system wanted to know, for instance, whether a Black woman was being discriminated against because of her gender OR her race. There wasn’t a framework for understanding how it could be both at the same time. Thus, intersectionality was born.

Intersectionality helps us understand that fatphobia and discrimination against racialized, trans, queer, disabled and other marginalized bodies are all deeply intertwined.

So it’s great to be a size-inclusive coach. But that also means understanding that multiple aspects of discrimination and marginalization compound each other, and how this effect may impact your clients.

Learn more: Racism and fatphobia

Learn more: Developing an intersectional coaching practice

It’s not as hard as you think.

Maybe you’re wondering: How can you possibly become an expert in body positive coaching, coaching trans athletes, working with people with disabilities, and anti-racism?!

This may come as a relief: You don’t have to be an expert.

First, you can turn to plenty of experts for help. Many of these activists have courses, books, and other resources, like the ones listed in the boxes throughout this article.

But what’s even more important, Mills says, is this:

Clients are experts in their own experiences.

Usually, you can learn directly from them.

That doesn’t mean it’s their job to educate you.

But you can listen to and engage with the lived experience of the person right in front of you, Mills suggests.

“Often, it’s not even that they need you to be really involved in their personal experience as their coach. They just need to know that you’re not going to devalue it.”

We have work to do.

Many of us have hidden biases, body image concerns, and areas where our awareness is lacking.

To grow into more inclusive coaches, according to Mills, we first must lose the “fix it” mindset. We won’t solve weight stigma, racism, or any other type of discrimination by changing the equipment in a gym or taking a course. (Though those can be good action steps.)

“When we try to fix problems, we’re trying to get a sense of control,” Mills points out. “And to meet people where they’re at, you need to lose that desire to control things and be open and receptive.”

And meeting clients where they’re at? That’s what matters most.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

1. Products – Data Briefs – Number 313 – July 2018 [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Sep 2]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db313.htm

2. Persky S, Eccleston CP. Medical student bias and care recommendations for an obese versus non-obese virtual patient. Int J Obes. 2011 May;35(5):728–35.

3. Foster GD, Wadden TA, Makris AP, Davidson D, Sanderson RS, Allison DB, et al. Primary care physicians’ attitudes about obesity and its treatment. Obes Res. 2003 Oct;11(10):1168–77.

4. Stone O, Werner P. Israeli dietitians’ professional stigma attached to obese patients. Qual Health Res. 2012 Jun;22(6):768–76.

5. Ferrante JM, Ohman-Strickland P, Hudson SV, Hahn KA, Scott JG, Crabtree BF. Colorectal cancer screening among obese versus non-obese patients in primary care practices. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006 Oct 25;30(5):459–65.

6. Ferrante JM, Fyffe DC, Vega ML, Piasecki AK, Ohman-Strickland PA, Crabtree BF. Family physicians’ barriers to cancer screening in extremely obese patients. Obesity. 2010 Jun;18(6):1153–9.

7. Brown I, Thompson J, Tod A, Jones G. Primary care support for tackling obesity: a qualitative study of the perceptions of obese patients. Br J Gen Pract. 2006 Sep;56(530):666–72.

8. Byrne SK. Healthcare avoidance: a critical review. Holist Nurs Pract. 2008 Sep;22(5):280–92.

9. Flint SW, Čadek M, Codreanu SC, Ivić V, Zomer C, Gomoiu A. Obesity Discrimination in the Recruitment Process: “You’re Not Hired!” Front Psychol. 2016 May 3;7:647.

10. Puhl R, Brownell KD. Bias, discrimination, and obesity. Obes Res. 2001 Dec;9(12):788–805.

11. Sabin JA, Greenwald AG. The influence of implicit bias on treatment recommendations for 4 common pediatric conditions: pain, urinary tract infection, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and asthma. Am J Public Health. 2012 May;102(5):988–95.

12. Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, Beach MC, Sabin JA, Greenwald AG, et al. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am J Public Health. 2012 May;102(5):979–87.

13. Emmer C, Bosnjak M, Mata J. The association between weight stigma and mental health: A meta‐analysis. Obes Rev. 2020 Jan 10;21(1):68.

14. Fortman T. The Effects of Body Image on Self-Efficacy, Self Esteem, and Academic Achievement. 2006 Jun 1 [cited 2020 Sep 2]

15. Cash TF, Deagle EA 3rd. The nature and extent of body-image disturbances in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 1997 Sep;22(2):107–25.

16. Markey CN, Markey PM. Relations Between Body Image and Dieting Behaviors: An Examination of Gender Differences. Sex Roles. 2005 Oct 1;53(7):519–30.

17. van den Brink F, Vollmann M, Smeets MAM, Hessen DJ, Woertman L. Relationships between body image, sexual satisfaction, and relationship quality in romantic couples. J Fam Psychol. 2018 Jun;32(4):466–74.

18. Wilson RE, Latner JD, Hayashi K. More than just body weight: the role of body image in psychological and physical functioning. Body Image. 2013 Sep;10(4):644–7.

19. Markland D. The mediating role of behavioural regulations in the relationship between perceived body size discrepancies and physical activity among adult women. Hellenic Journal of Psychology. 2009;6(2):169–82.

20. Sarwer DB, Thompson JK, Cash TF. Body image and obesity in adulthood. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2005 Mar;28(1):69–87, viii.

21. Tylka TL, Wood-Barcalow NL. What is and what is not positive body image? Conceptual foundations and construct definition. Body Image. 2015 Jun;14:118–29.

22. Trabulsi, J., Schoeller, D. (2001). Evaluation of dietary assessment instruments against double labeled water, a biomarker of habitual intake. American Journal of Physiology: Endocrinology and Metabolism, 281(5): E891-E899.

23. Crenshaw KW. Demarginalising the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of anti-discrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and anti-racist politics. Univ Chic Leg Forum. 2011 Jan 1;140:25–42.

If you’re a coach, or you want to be…

Learning how to coach clients, patients, friends, or family members through healthy eating and lifestyle changes—in a way that’s personalized for their unique body, preferences, and circumstances—is both an art and a science.

If you’d like to learn more about both, consider the Precision Nutrition Level 1 Certification. The next group kicks off shortly.

The post Are you body-shaming clients? How even well-intentioned coaches can be guilty of “size-bias.” appeared first on Precision Nutrition.

from Blog – Precision Nutrition https://www.precisionnutrition.com/size-inclusive-nutrition-coaching

via

Holistic Clients